Pauline Hafsia M'barek interviewed by Paula Grimm and Benjamin Roth

PG, BR: You’ve been engaged with the holdings of the Agfa archive in the Museum Ludwig. When we visited the collection we learned that you were initially interested in The Pencil of Nature by William Henry Fox Talbot. How did the switch to the Agfa archive come about and do you see any connections?

PM: The project hasn’t actually changed fundamentally, but it’s grown and been updated. I was very interested in Talbot’s images at first, because, often, only traces of the images can still be found on the photographs and many illustrations have faded and are barely recognizable. These chemical stains and streaks lay bare the material production conditions of picture-making. When I asked to see these objects in the Museum Ludwig, the conservators told me that, due to their fragility, these highly light-sensitive photographs can no longer be exhibited. That set me onto new trails and I started dealing intensively with the fragility of photographic images, or respectively the various influences and forms of their degradation.

Naturally, I wasn’t allowed to touch anything in the museum’s depository myself and could only do research via other people’s hands. To do that, I had to know what I was looking for in advance, which was difficult for me. After that I pretty quickly ended up in the Agfa advertising archive, in which I was able to do research independently. That’s a very small space full of file folders and also some cardboard boxes that haven’t been sorted yet, they still had to be inventoried. I went through the material for months. My interest in photography – not primarily as representation or indexical sign, but as complex materiality – then led me to the production conditions of photography.

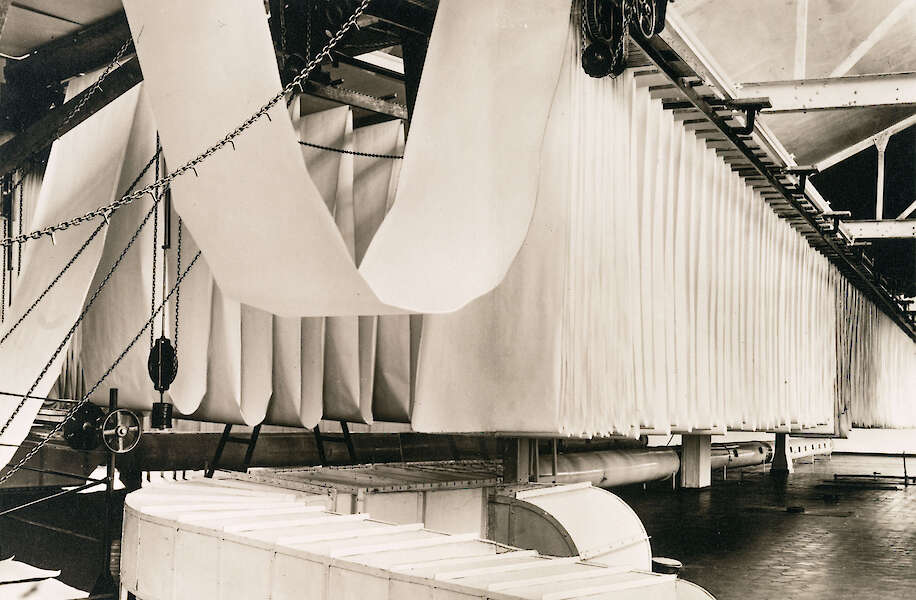

Advertising images can be found in the Agfa advertising archive, of course, but also depictions of the industrial production of paper, photographic film and emulsions. There are also many scientific investigations concerning image flaws that become evident after developing: where do they come from? Is it because of the composition of the gelatine and where do we find better gelatine? How can we make the emulsion even more sensitive? The creation of the image or its visibility and the chemical and material conditions of the image carrier or its chemicals are of course closely related.

PG, BR: Have you already worked in archives in the past, or is an examination like the one you’re doing with Artist meets Archive new for you?

PM: I always work in highly complex research processes which often include archive material as well. For example, between 2010 and 2013 I realized an extensive project on a former Belgian colonial museum, the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, and engaged with ways of presenting colonial objects in museums. You could say that generally, I’m less concerned with the objects themselves than with the question of how we treat these objects and lend them meaning. I’ve never worked as specifically with and in an archive as in the Museum Ludwig, though.

It was a very exciting experience for me, because archives are always knowledge laboratories and there are lots of trails you can follow. The material can be interpreted in so many diverse ways – chemically, historically, iconographically – which means that there would need to be multiple classification systems available in order to categorize it in any kind of way. To me, researching in the Agfa advertising archive was very inspiring, because it took me into the heart of the Agfa plant: took me into the photograph’s materiality, detailed microscopic explorations and descriptions of substances, but also to toxic, historical documents of the company’s NS history.

At the same time, physical contact with the archive material is really important, because that’s the only way its different aspects become visible. Depending on how you hold a photo up to the light, you can learn a lot about the paper’s surface texture, for example, by the way the light reflects off it. Or you can better detect processes of degradation, like silver mirroring for example. The back of the photo often provides information about its origin story, you find notes on the images, historical information, and dates.

PG, BR: Will your engagement with the archive have any effects on your creative output in the future? To what extent has your view of photography already changed?

PM: My view of photography has of course changed a lot as a result. I’m not a photographer, after all – that’s only a part of my practice. It was really exciting for me not only to be in the archive but – based on my observations in the archive – to be extending my research to the Museum Ludwig itself as well. So it’s not only about the archive material, but also the people involved and their working practices: from restoration and building services, through pest control to the cleaning staff, but also the building’s structure – for that I was in the basement and even on the museum’s roof.

This look behind the scenes was extremely stimulating and exciting, because it made the complex interlocking of the various actors and practices tangible for me. Through it, I fairly quickly came into contact with some highly current issues, like climate change for example, with its disastrous floods, periods of heat, water scarcity or the new parasites. The museum has to react to all of that, of course. In this respect, I think that this very comprehensive research and, above all, the interaction and dialogue on site will have a strong influence on my future working practice.

PG, BR: You talk about technical aspects, chemicals, toxic elements, and the reciprocities between humans and photography as being factors you’re interested in. Can you specifically say what fascinates you about this interplay between human influence on photography and photographic influence on humans?

PM: I’m interested in the materiality of photography, because it is never detached from the exterior – on the contrary, it’s made up of substances from the environment that are extracted. The human body is also not only visually depicted, but is deeply involved in the industrial production of photographic material and its recording and reproduction devices. But it’s also involved in the degradation of photographs, which progresses more quickly through contact and body heat, for example.

What was extremely exciting for me, along the way, was the toxic side of Agfa’s corporate history, because it is strongly associated with the history of chemical industrialization, pest control and Nazi war crimes. Incidentally, connections like these are even continuing in the digital age, as we’re seeing in the Ukraine war at the moment. Rare earths are an essential raw material for our highly technologized life – for our touchscreens and smartphones. Our shiny screens conceal stories of the most brutal exploitation of human labour, landscapes and animals, with extremely disastrous consequences. To me, all that is contained within this interplay.

PG, BR: Your gaze also shifts through the objects’ different visual layers, from the molecular level such as the chemicals to the overall view. What constitutes this change of perspective?

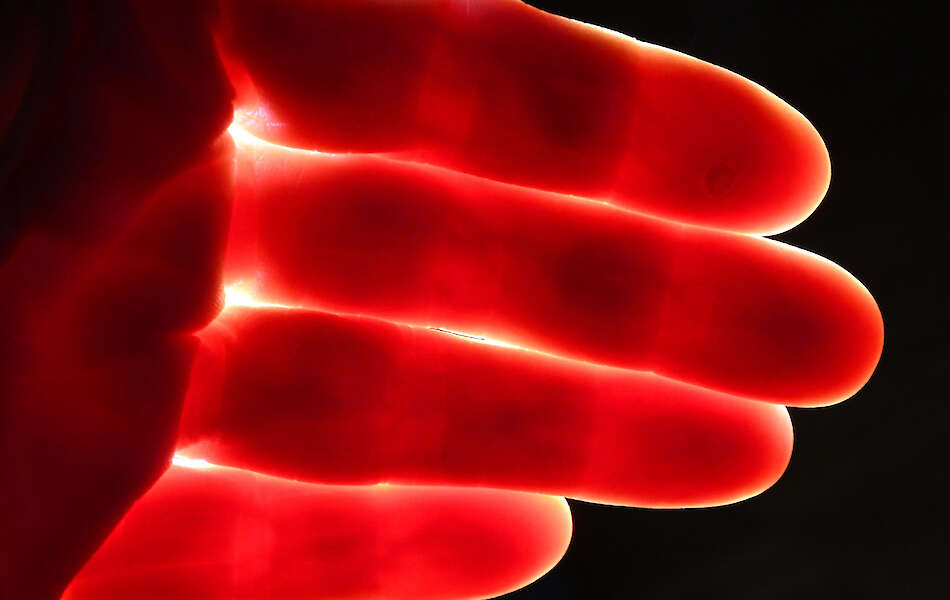

PM: To me, scaling the view from the macrocosmic to the microcosmic is always political as well. A look inside the material reveals how leaky, how porous and vulnerable objects and bodies are and how often you can detect comparable molecular structures and functional mechanisms. In close-up, we are no longer the sovereign subjects, superior to objects, that we’d like to be, but flaky, vibrating, material, ephemeral components of the world, with which we’re hence totally entangled.

For me, though, a proximity also arises through engagement that’s as open as possible. For example, through intense dialogue with the people who are closest to the archived objects and who consider these objects from very different perspectives, depending on their working practice. A dialogue arises: for example, I speak with the people in charge of the ventilation system down in the bowels of the museum, get shown the microparticle filter on the air conditioning system, and learn all sorts of things about environmental pollution in the process.

PG, BR: Besides photography, you also work with drawings, videos, sculptures or light staging – so very multi-medially. Can you give us a little teaser on what the exhibition’s going to look like?

PM: I generally work experimentally and in an open-ended way within a very organic working process, which is supplied by diverse contexts and references. Extensive research networks arise as a result, which I can draw from to develop a constellation of different works.

The exhibition begins with the examination of light as a raw material of photography and its chemical reactions, and deals with the agents of chemical degradation in the form of exhibited microparticle filters, papers made out of museum dust, and living parasites. Within a display, documents from Agfa production, exhibition equipment and photographic materials are shown. The exhibition ends with the projection of shimmering retinal images and a video showing the reflection of the museum in a seeping drop of ink.

PG, BR: Did you also toy with the idea of introducing interactive aspects?

PM: To me, the concept of the interactive artwork is a bit problematic. Just because I can touch something, that doesn’t necessarily mean actually getting closer to the things. Despite the comprehensive research that underlies my work, naturally I also want it to be tangible at an intuitive, sensory level. For me, it’s about a form of contact or interaction that isn’t limited to the sense of touch, but is in fact much more comprehensive – that is, it gets the body, the gaze and the beholders’ movement involved.

Interaction can also mean that something close is being referenced. For example, a video will be on show that depicts the macro shot of a fingertip, with small beads of sweat forming on the whorls. This close-up of the porosity of the skin’s surface naturally has some kind of effect, because you don’t contemplate your own body in that way otherwise and you don’t see what’s going on beneath your perceptional threshold. In this respect, interaction for me is not at all limited to the fact of touching something concretely, but for me it is more about getting close to things themselves, and, in doing so, perhaps move other people too.

PG, BR: Thank you for this very exciting insight into your work and also for taking time to talk to us. We’re both very keen to see your exhibition and already looking forward to its presentation in the Museum Ludwig.

The interview was conducted online in German on 26 February 2025.

Pauline Hafsia M'barek's exhibition "Entropic Records" at Photoszene-Festival 2025