Andrés Galeano interviewed by Maxi Gaiser and Emily Hagedorn

MG, EH: What’s the meaning of Mission “X-DBA-00408”, as you write on Instagram on your planned project about a stone fragment of Cologne Cathedral? Is this an archive signature or an idea that you had?

AG: For one thing it’s an idea that I had, but yes, you guessed correctly – this is also an archive signature.

My work as part of Artist Meets Archive is all about a piece of cathedral stone that was in space. It was located in the foyer of the Cologne Cathedral Administration, in a showcase, and its story fascinated me straight away. It was there as a kind of souvenir, without an archive number. I asked Matthias Deml, then still deputy director and, since January of this year, director of the archive, whether we could give the stone an archive or inventory number. He then thought up this designation. That was a challenge, because the stone is no ordinary object in the Cologne Cathedral Works Department Archive (DBA, Dombauarchiv), where people work with photographs, but also paintings, works in glass, or plaster models. The “X” stands for miscellaneous objects, “DBA” for the construction archive, and “00408” stands for the distance (in kilometres) between the ISS, the International Space Station, and Earth.

MG, EH: You’ve already gathered experience in the field of archive work in your artistic practice. What made the Dombauarchiv particularly interesting for you? Are there any standout features in comparison to your previous work with archives?

AG: It was special, since it was the first time I was invited by an archive and got paid for my work. Normally it’s the other way around.

When you’re an artist and interested in a topic, you do some research on what archives might have materials on it. It’s about self-initiative. It’s really not easy to get at some (photo) materials. Archives have their rules and protocols and it could take you up to two years to gain their trust. And after that you apply for grants, to fund the project. And this time, right, it was the other way round: I applied for a project again and then all the doors in the Dombauarchiv were open to me.

The archive is highly complex. It covers everything – from the Three Magi collection to the stone and archaeological collections. 85 people are employed in the cathedral workshop. From archaeologists through photographers to stonemasons and restorers. I wanted to use the opportunity to work with all of these areas of expertise and professional people. During the research I spent almost a day with each of these specialists, having it explained to me how this world works. What I now do, practically, is I run through the project on the basis of the various jargons: from the scientific, technological language of stone restoration to the aesthetics of the astronauts’ world and the ESA.

MG, EH: During our tour through the Dombauarchiv we gained an insight into the size of the collection. We were also shown the showcase in which the stone has been kept since its return from space over ten years ago. What moved you to devote yourself to this rather unremarkable fragment and its time in space – and hence put it back in the spotlight, so to speak?

AG: The cathedral stone’s story was particularly exciting to me. At the end of the day, every stone in the cathedral is striving to reach up to the heavens, both physically and metaphysically. And this one stone manages to do so. It manages to fly up high, 400 kilometres away from Earth into space. And that brings me back to my interest in vernacular photography. When I deal with this form of photography, I’m always working post-photographically, that means with found pictures that other people have taken. The stone was refuse. Just like the pictures I find at the flea market. Well, they’re not refuse at the flea market yet, but they’re about to be. These photographs are at an intermediate stage there, raising the question of what kind of value they have in the first place.

And now we get to the core of the thing that fascinated me, namely that the ESA asked the City of Cologne for a stone. The communications director of the ESA had been thinking about how he could use a marketing strategy to draw Cologne residents’ attention to the ESA. In the process, the idea came about for astronaut Alexander Gerst to take a Cologne flag and a stone from the cathedral with him into space, and then build the stone back into the cathedral again at some point. All this was “top secret” at first – employees at the Dombauarchiv had no idea what the stone was going to be used for, and sent a selection of three. Judging by photos I analysed, the stone that was subsequently handed over was a different one from the one that went into space.

MG, EH: On your website, you write that engagement with the transcendental is something that often characterizes your works. What’s the relation, do you think, between photography and the firmament, where is the sacred evident, and how do you realize that artistically? Were you perhaps able to develop new thoughts on the subject as a result of your time in the Dombauarchiv?

AG: Yes, definitely. I’ve already visited various kinds of archives before, working and doing some research, for example with photographs of the sky, in meteorological archives for instance. This time, we went a bit further – or higher.

I deliberately applied for the Dombauarchiv because it was about the sacred, for me. My original idea went in another direction, but I just took an open approach to the project, visited the archive and looked for inspiration. I found it in the Dombauarchiv when I took a look at the topic of relics. I had a long conversation about it with the Director of the Cathedral Treasury, Leonie Becks. She explained to me how relics are presented and conserved, but also what a relic is in the first place. She also showed me lots of contact relics. Basically, these were scraps of fabric of bits of paper which were rubbed against the main relics and then sold, complete with authenticity certificate.

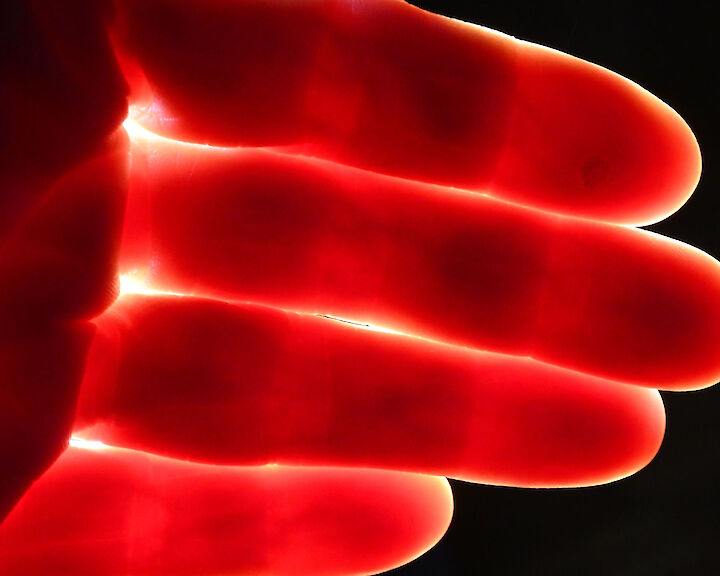

When you touch a relic, basically you’re supposed to get the “powers” of these relics. That is part of religion. I produced a series of drawings of the cathedral stone that is called Reliquien. You can see the stone’s six sides in these. While drawing, little grains of sandstone trickled onto the paper, which I then glued on. That is, this paper was provably in contact with the stone that was in space – like a contact relic. I then recorded all the authenticity certificates on the back. We have, for example, the stamp of the Cathedral Workshop, the Cathedral Treasury, and one more, which I designed myself.

The sacred is part of the art world, too. The stone was a stone fragment, which wasn’t important or valuable, but it became that, and that’s the story I want to tell. What makes an object special and what does that have to do with sacredness and aura? What makes an object important? What makes an object art? What makes an object holy? So my concern, in my project, is also the stone’s re-auratization. Normally, a stone like this one would never get so much attention. The original stone will also never get put on display in the exhibition, in reality. Why is that? Exactly as with relics, this has to do with superstition. You have to believe in relics, you have to believe in art, you have to believe in a photo – right?

MG, EH: Your piece AI Sol demonstrates that you usually work with a certain irony and exceed the medium’s metalevels. What strategies do you use in your engagement and where do you see opportunities or even challenges in this approach?

AG: The metaphorical is always important and the sky is basically a primal metaphor for transcendence. When I engage with the photographic medium, I’m particularly interested in that. Viewed historically, photography is the medium which promises us a certain eternity and to that extent, perhaps, something divine as well, by recording light and the moment. When I deal with found (sky) photographs from albums, I’m dealing with allegedly bad photos. Now, these aren’t particularly aesthetic photos, but the people who took these photos took them because this moment was important to them. And when I then abstract the sky in my compositions, I’m paying tribute to this attitude and these photographers, by only talking about this transcendence or only showing the sky. For that reason, I see an inherent connection between the sky as a metaphor for transcendence, and photography.

For me, the project has also opened the door to another materiality in addition, namely stone. I’m not a sculptor and really don’t know about sculpting, but I am very curious to know more. Every project opens new areas, which also bring me knowledge. But, as far as I’m concerned, the topic is always the same, including in this case. It is about a loaned stone, which was in space, and Cologne Cathedral is associated with the metaphysical sky (heaven). Because of that, my project has to do with religion on the one hand, and with archives and also the everyday on the other.

MG, EH: Religion, archives, everyday, astronauts and in addition, questions of transcendence. How will you be processing these references in the exhibition?

AG: The exhibition is taking place in Cologne Cathedral. That’s for various reasons: for one thing, this way, many different people will come face to face with the work. Because I’m also concerned with disseminating this story. And on that point I also need to use marketing strategies. For example, I’ve designed patches, like those worn by astronauts, only with the cathedral stone on them. Postcards and a blue 3D print of the stones in 1:1 scale will likewise be available, and the Cathedral shop will also be part of the exhibition. To me, all the attractively priced souvenirs are an important part of the exhibition. Firstly, in order to disseminate the story; secondly, because a church, of course, has the sacred, but it precisely also has the banal, the everyday. The two go hand in hand, which is why this dialectical relationship is part of my work.

The exhibition objects will probably be lying on a tarpaulin, without following any particular organizational structure, because in space, under zero gravity, there is also no up, no down, no right, no left. We want to convey that feeling in the exhibition. The idea is for people to be lost at first. Exactly like when they visit an archive. It doesn’t operate chronologically, but associations arise; a story that has to be reconstructed. And there are gaps and places where it all doesn’t quite fit. Artistic freedom also plays a role there. We are artists, not archivists. Given that, we can approach things differently and perhaps also more freely.

MG, EH: Many kind thanks for the conversation and revealing insights into your work process, Andrés. We’re already looking forward to the exhibition and can’t wait to discover the story of the cathedral stone!

The interview was conducted online in German on 12 February 2025.

Andrés Galeanos exhibition X-DBA-00408 during Photoszene-Festival 2025