Jimmi Wing Ka Ho interviewed by Rebecca Böhm, Carla Hamacher and Luzie Ronkholz

RB, CH, LR: The Artist Meets Archive program brings together artists who engage with archival material. However, there are numerous approaches on how to, and various motivations as to why artists choose to engage with archives. First of all, what prompted you to apply to the program and why did you choose the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in particular? Was this your first collaboration with an archive? And secondly, how would you describe your approach to working with an archive?

JH: I chose to participate in the Artist Meets Archive program because the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum (RJM) holds objects in its collection that bear witness to the colonial history of China. In many archives there is a lack of representation of China, because they focus on Southeast Asia and Japan. This is a critical gap I want to address with my research. When I applied to the program, I visited several institutes and did research on China’s colonial history. I found out that engaging with the collections of the RJM could be particularly interesting for me, because there are relations to my previous work which talks about the colonial history of Hong Kong. Here, I was looking into the British Imperial rule over China. The RJM is also looking at colonial histories, but of course they are focusing on the German colonial past.

So, I talked to the curator of the photographic collection, Lucia Halder, who sent me an index of photographs from the collection. First, I tried to find something about Hong Kong, but they don‘t have anything related to its colonial history, though they have something about China which stirred my interest further. In particular, they have visual records of the Chinese city of Qingdao during its German occupation from 1889 to 1914. I tried to find out more about the historical background of Qingdao, especially about its environment and the architecture and furthermore about the colonial period. My research was guided by several questions: Which records of Chinese colonial history does the RJM have in its collection and what is missing? What does the absence signify? And how can I use the archival materials in my own work?

When I was selected for the residency program, I tried to get an overview of the archival holdings. Interestingly, the materials related to Qingdao had never been fully explored before. They received this specific collection right at the establishment of the museum and after some digitalisation work, it had been left largely forgotten for many years. It is a huge collection that holds a lot of information about the colonial architecture of Qingdao. Some of those buildings still existed when I travelled there shortly after my residency in Cologne.

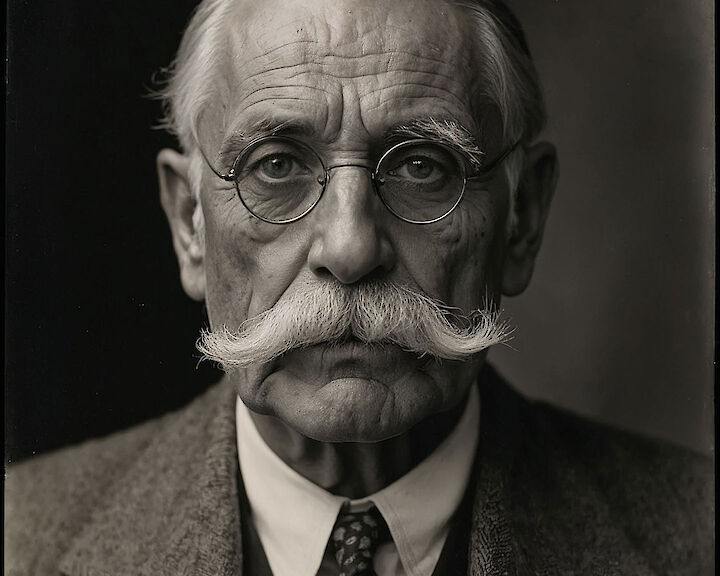

I found a lot of information behind the pictures – on the back of each photograph. They stem from the image archive of a magazine called Kolonie und Heimat (Colony and Homeland). It’s a colonial magazine that was published by the Organ of the Women's League of the German Colonial Society and contains a lot of uncomfortable pictures. My research has driven me to see these images as representations of the power of Germany’s colonial history and how they were used for propaganda purposes. The articles on Qingdao try to show how beautiful the city is and how suitable it is for German immigrants and tourists. They wanted German people to come there and settle down. Thus, they invested money to build a modern city and claimed it to be “the cleanest and healthiest” city in Asia. And then there was also a military rivalry between Germany and Great Britain that had influence on this, as Hong Kong was occupied around the same time. Germany in a way mirrored how the British occupied Hong Kong in choosing Qingdao as the nearest harbor city.

Once I received the digitized material from the museum, I tried to categorize it. For example, they have architectural images, a book on urban development as well as maps with sightseeing spots. This categorization has been immensely helpful for my project. I also learned about a person in Cologne who was born in Qingdao and studied its colonial past before me. He lived there as a child in the 1930s and 40s and returned to Germany with his parents when he was 12 years old. He had collected a lot of information and materials about the colonial history of Qingdao. Unfortunately, he passed away a few years ago. But we were able to talk to his son and learn about what life in Qingdao was like at that time and what the city looked like.

RB, CH, LR: So, you first had a look at the archive and starting from this, you developed the idea of going to Qingdao and taking photos there?

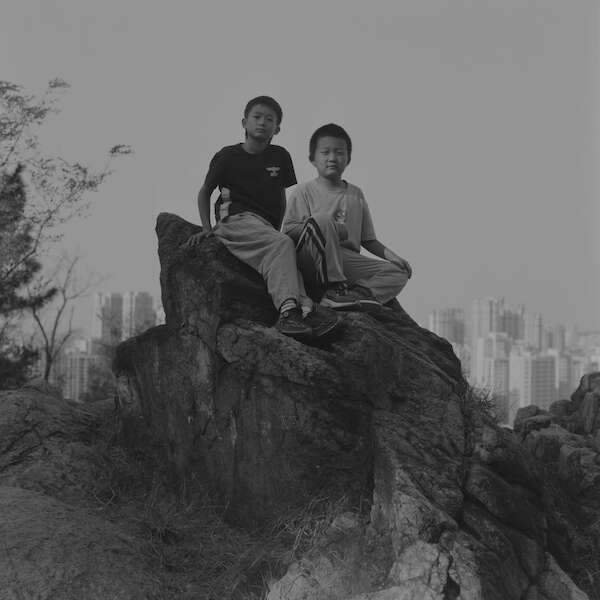

JH: Yes. I think it’s quite similar to my work So close and Yet so far away where I also used archival material to show how the place changed. I went to Qingdao in September 2024, after my residency stay in Cologne in July. In the pictures I took there you can see some colonial buildings that still exist. Today the atmosphere is like a mix between Western and Chinese culture. For instance, when I was visiting, I saw so many German-style architectures with Chinese decorations added to them or converted for different purposes.

For me the archive was the entry point to this engagement with the history of Qingdao. I once went to Qingdao with my parents when I was a little kid, but I have very few memories about it. So, my first impressions of the city were shaped by the archival images of the RJM. This is why I made the trip to Qingdao: I wanted to compare the real city with those images. I wanted to find out how much truth and what level of propaganda lay behind them.

RB, CH, LR: You’ve just mentioned So Close and Yet So Far Away, a previous work of yours that explores the history of a place, Hong Kong, and its people. Your current project is also centered around a place, Qingdao. Both cities are linked through their colonial past(s). Do you see any other connections between these projects and your approaches, and if so, how would you describe their interrelations? Also, speaking about the people: Could you tell us more about the encounters you had?

JH: It’s hard to compare the two projects because they are about very different cities. When I was in Qingdao for the first time, I learned that the people there are very sensitive about the topic of colonialism, because there is a lack of education. They are surrounded by colonial architecture and know what the government has told them about it. But there is no deeper discussion. They try to erase colonial history from their “original“ history, especially the Japanese colonial era. Somehow, they feel like the Germans had a great influence on Qingdao because they built up everything and brought a lot of infrastructure.

RB, CH, LR: Migration and belonging play a role in your own biography. To what extend do you try to incorporate your personal memories and experiences into your photographic practice?

JH: These topics play an important role in my previous project So Close and Yet so Far Away, because it is about my experience of migrating from Hongkong to the UK, but not so much in the project about Qingdao. There, I navigate as an outsider, observing the city from a distance, how it is shaped, what things are partially forgotten. The focus lies on Qingdao’s history, aiming to create new perspectives on it, without focusing on my personal background.

RB, CH, LR: The questions of migration and belonging are politically charged, not only in China, but also in Germany. Here many gaps remain in the national memory of colonialism, also regarding the German colonial rule in China. Would you say that you are pursuing your current work with a political – perhaps even activist – intention? And have you ever encountered resistance because of your current work’s exposure of such sensitive topics from the past?

JH: The things that happened in history are not forgotten and hence still affect our daily life. The protests in Hong Kong since 2019 are one of the reasons why I stayed in the UK and they made many other people move there as well. This situation is closely related to my work, because I try to bring the history and the hidden memories of the people back to light.

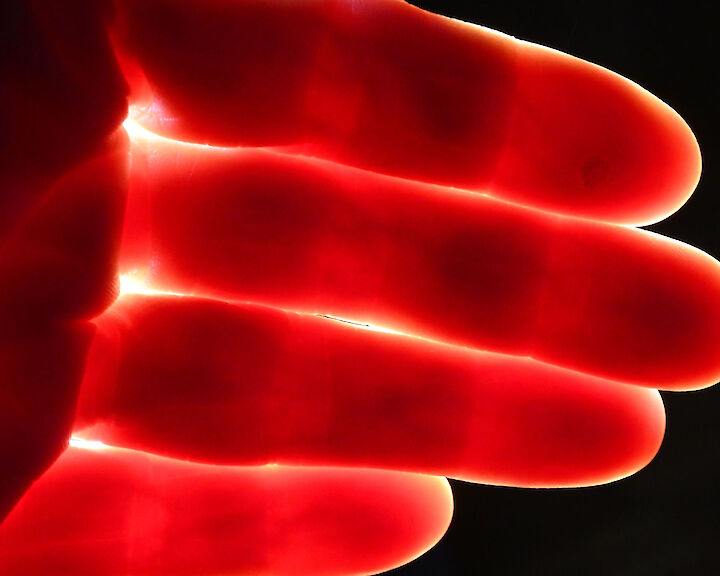

One of my chapters in my project about Qingdao refers to a story about the underground drainage system that was built during the German occupation. It’s a story everyone knows about: It says that the Germans left repairing parts wrapped in oil paper after the occupation ended. So, in case parts of the drainage system got broken, the local people could fix it. The people believe in this story, thinking that the Germans just brought positive things like technological development and wanted to help the local population. But of course, their main interest was to gain more power and promote it. As an artist I can use this story and revert it. By using the archival material of the German self-representation and combining it in an installation that also includes oil wrapping paper and thus refers to this oral story.

RB, CH, LR: Ethnological museums are under pressure to radically rethink their exhibition practices. What possibilities do you see in artistic research in their collections? Could you give us an insight into how you will present your work for the upcoming Photoszene Festival?

JH: I think there are still some challenges about how to deal with colonial history right now. Regarding the RJM we discussed a lot on how to use and sample the colonial materials as the museum has a huge collection of photography dominated by violence. Artists have the opportunity to reinterpret the images without merely reproducing them. Art can intervene in the cracks and absences of museum narratives to create new perspectives. In my project, I want to fill the gaps in collective memory by expanding the collection beyond the museum.

After I went to Qingdao, I got a different understanding of the city and its confrontation with its history and also how archival material can be a site of the representation of power. The city of Qingdao and the RJM are somehow both undergoing a process of decolonization, but in different ways. In China, much is erased and rebuilt, making the past less visible. They don’t want the citizens to know about the past. In contrast, the RJM aims to make the colonial past visible and encourage reflection.

In the Photoszene Festival I will present my project in different chapters. As an intro, I will show a video to let the people know what the city of Qingdao looks like. It is inspired by the novel Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. In this novel Marco Polo is talking to the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan in China using different stories of people to describe cities to him. For my video I am also using different stories and ways to talk about Qingdao, but without actually mentioning the city. I’m trying to transfer my experience of travelling to Qingdao into the people’s stories and the conversations I had with them. In another section I will display the photographs I took in Qingdao to show what it looks right now. I also photographed the people I met there and interviewed them about what they know of the city’s colonial history and what they don’t know, how they feel about the colonial architecture, and whether it still holds any meaning for them. Also, the exhibition will include the installation mentioned earlier. It refers to the underground drainage system and the story people tell about it. For that chapter, I will use oil-wrapping paper, archival material and sound, to make the hidden story visual – and audible – for the audience.

RB, CH, LR: Thank you very much for these special insights into your work! Now we are even more excited and already looking forward to the opening of the exhibition!

The interview was conducted online in English on 17 February 2025.

Jimmi Wing Ka Ho's exhibition "Invisible City" at Photoszene-Festival 2025