Sabine Voggenreiter is a curator, designer, and influential figure in Cologne's cultural and design scene. With the design festival “Passagen,” which she founded in 1989, she established a decentralized exhibition format that brought design to unusual locations in the urban space. In the early 1990s, Fritz Gruber asked her to revive the Internationale Photoszene Köln (Cologne International Photo Scene) – a task she undertook with great success. Between 1991 and 1996, as director of the Photoszene, she was responsible for an annual festival that attracted a great deal of attention, opening up new formats, alternative exhibition venues, and a broad public for photography.

In this interview, Sabine Voggenreiter talks about the beginnings of her involvement with the Internationale Photoszene Köln, her collaboration with Fritz Gruber, and the challenges of reorganizing and rethinking the festival. She discusses the dynamic cultural landscape of Cologne in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as the connection between photography, design, and architecture.

How did you originally get involved with Internationale Photoszene?

I studied art history. Even back then, my focus was quite contemporary—not Raphael or Titian, but contemporary topics such as design, photography, and video.

Photography was omnipresent in Cologne, especially in the 1980s.

The scene was strong, both in art photography and documentary photography. I was always involved in this scene, but initially focused more on design in my professional life. After graduating, I founded the design festival “Passagen” in 1989. It was a decentralized festival, spread throughout the city, often in everyday locations – that was new at the time and immediately attracted a large audience.

This work brought me into contact with the photography scene. Fritz Gruber approached me directly at the time and said, “What you're doing at Passagen is something we could use at Photoszene.” The International Photoszene had fallen dormant at that point. I took it over in 1991.

What was the situation like when you took over the International Photo Scene?

The first International Photo Scene took place in 1984. At that time, Photokina still existed, and the Photo Scene took place every two years. After that, two more events took place, but at some point there was a break. I don't remember exactly why – perhaps due to a lack of funding. I took over the management in 1991. The budget was tight, but I was already used to that from Passagen. I developed a concept: a publication concept, a financial concept, and, of course, a content concept. Everything was done in collaboration with the participants who wanted to be involved. There were large meetings at the Museum Ludwig, where everyone who felt connected to photography came together.

What was your approach to organizing the Photoszene?

I adopted many of the things that had already worked at Passagen. For example, a small booklet with a city map and an overview of all the exhibitions. We were able to print a large number of copies—at least 50,000—and distribute them throughout the city. This gave us a completely different public image. Photoszene had previously been a program for insiders, but now it became visible to a wider audience.

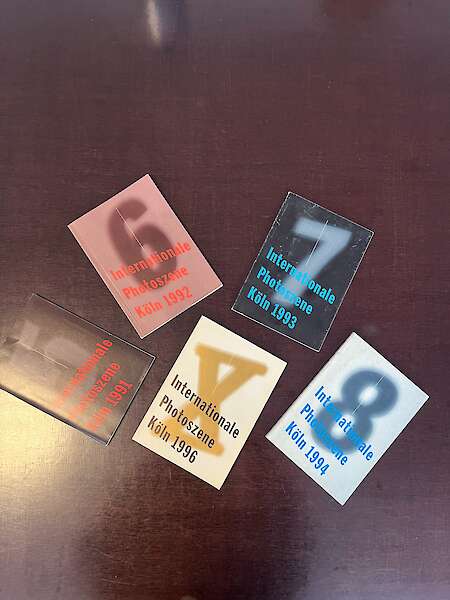

From 1991 onwards, we held Photoszene every year, no longer just in parallel with Photokina. I organized the festival six times until 1996, and it grew every year, always according to the motto: After the game is before the game. The booklets became thicker and thicker; by the end, we had over 100 projects at the tenth Photoszene, for example. That made the scene very dynamic.

What was the connection to Photokina like at that time?

There was some overlap in personnel. Fritz Gruber had built a bridge between the trade fair and artistic photography with his picture shows. Companies such as Kodak were also involved—with their own exhibitions and cultural programs, but of course also through sponsorship. This provided the Photoszene with additional resources.

Are there any moments or encounters that have remained particularly memorable for you?

The close collaboration with Fritz Gruber was very important to me. We already knew each other, but it was a privilege to exchange ideas with him on a regular basis. It was also important to me that the entire scene, not only the mediators but also the photographers themselves, could participate. Not only those who had been curated by others, but also those who wanted to participate on their own initiative were able to get involved.

That hadn't been the case before. This created a momentum of its own. We used locations that no one would have previously associated with photography—brownfields, industrial buildings, empty swimming pools. It was an exciting time.

How did you experience Cologne as a creative space back then? What potential did these off-spaces have for you?

Of course, I was still under the impression of the 1980s in Cologne, when Cologne was an absolute art capital. The gallery scene was also enormous and already occupied some places that were atypical for a classic “clean” gallery. There were fluid boundaries between art, photography, video, and performance. This experience had a strong influence on me. Once you've experienced that, you can't imagine classic white cube exhibitions anymore. For me, it was clear: I wanted to go out into the city, into indoor swimming pools, industrial buildings, onto the streets. Entire neighborhoods such as Ehrenfeld, which was still very rough at the time, or the Rheinauhafen became exhibition venues. Even in the Belgian Quarter, you could still find such wastelands at the time.

You launched a competition for the 1995 International Photo Scene together with Ulrich Tillmann. What was it about?

In 1995, a year without Photokina, we wanted to bring in some new momentum. We announced a competition that was about staging photography in a new way – beyond classic hangings. It was about innovative presentations and direct encounters with the artists. Over 40 exhibitions took place as part of this competition: in subway stations, swimming pools, but also in very small private rooms – everything was included. It was a completely new experience for all of us and was also very well received by the audience.

Did you continue with it?

Originally, we wanted to, but we didn't want to repeat the format too often so as not to water it down. The competition provided impetus that later flowed into Internationale Photoszene 10 – my last edition. After that, there were differences of opinion, including with the cultural office, which wanted to take a more conservative approach. I think it was just too wild for them. I resisted at first, but in the end I decided not to continue. Maybe compromises could have been made, but I didn't want that. I would have liked to have ventured further experiments.

I would like to talk about the interface between the different disciplines in which you work. What parallels do you see between design and photography? What appeals to you about combining the two?

I have always thought of design, photography, and later architecture as interconnected.

I started my career with the Passagen festival, the Photoszene festival came along soon after, and then I founded the architecture festival “Plan” in 1999. For me, the three disciplines belong together—whether in presentation, communication, or discourse. Photography is, of course, essential for depicting and communicating design and architecture. I later brought many architectural photographers who had exhibited at Photoszene to the architecture festival. There are very different ways of photographically depicting and staging these areas – that remains exciting.

Can the photography scene learn from the design scene – or vice versa?

That's a good question. Design is often more commercially oriented than photography—at least outwardly. But there are many overlaps: communicating design is virtually impossible without photography. Many designers have developed their own unique visual language—far removed from classic advertising photography. I find this staging exciting. There is a lot to learn from each other, especially in the area of presentation and communication.